"It isn’t important what white decision makers say when they say we’re making progress in race relations, what is important is what Black people perceive."

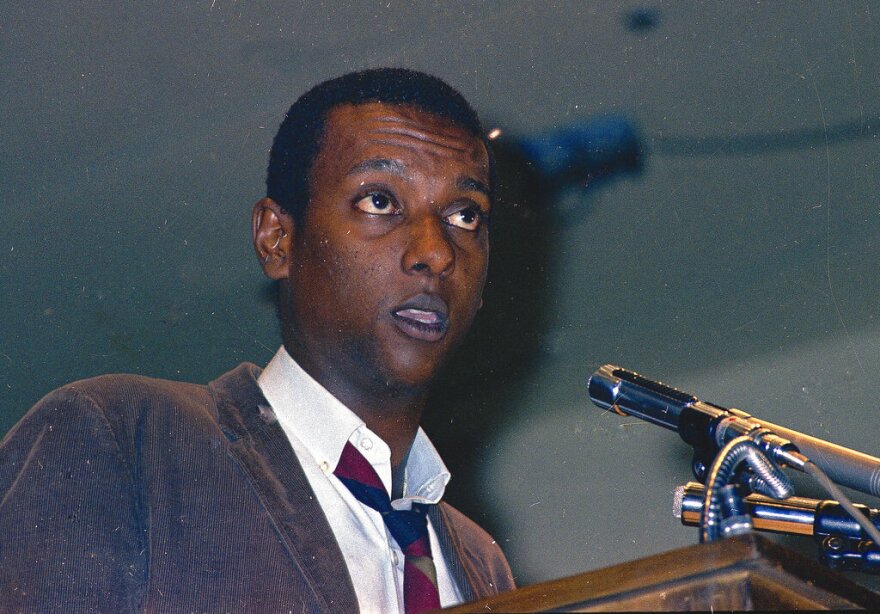

A month after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, political scientist Charles V. Hamilton speaks at Grinnell College during a memorial symposium. There are many origins to the Black Power movement, but Hamilton and his colleague Stockley Carmichaelelevated it with their 1967 book Black Power: the Politics of Liberation in America. He says Black Power can organize Black people’s rage and force answers to hard questions.

On the sixth episode of From the Archives, Hamilton speaks in 1968 about Black Power as a viable alternative. Peniel Joseph holds a joint professorship appointment at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and the History Department in the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Texas at Austin. He says Charles Hamilton is trying to ease racial tensions with coalitions, but also Black political self determination.

From the Archives was made possible through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The transcript was produced using AI transcription software and edited by an IPR producer, and it may contain errors. Please listen to the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

What I'd like to do is to deal with this subject in three parts. First, I'd like to talk aboutBlack Power, and its relationship to two major concepts: the concept of alienation and the concept of political legitimacy.

Indeed, theKerner Commission Report indicated that Black Power was a kind of throwback toBooker T. Washington, and a retreat from challenging America on the question of race. I think that this is absolutely incorrect. And I think that if I let the record show at the outset, that I simply disagree with that treatment of Black Power by the commission, then I think that will be sufficient comment at this point.

Secondly, I should like to deal with Black Power, as indeed the Kerner Commission Report did not deal with it. I should like to deal with it, in terms of its relationship to the process of political modernization. To show how, in a real sense, Black Power is not a retreat from, but an engagement of.

I should then thirdly, like to deal with some very specific, in by way of example, programs pursued by those of us who style ourselves as Black Power advocates.

Now, that's my three part approach to the subject. The first two parts are clearly not what one would expect, in terms of a discussion of Black Power, it's very obvious, it's very clear, that we come to a session of this kind on the topic like Black Power, and we have certain kinds of notions what we're going to hear. Well, I can satisfy many of those notions by using the word honky three times in a row. Or I can shout 'Burn Baby Burn' right now a few times, or I can give a quick 20 for one speech, that is to say, for every one of us, we'll get 20 of you. And I can be done with that. But at least the record will reflect that. The point I want to make here is that many of us, Carmichael included, have a notion about the clear, intellectual academic base of Black Power. And we have no intention of letting anyone relate to this subject simply because it is a glamorous, dramatic, possibly ephemeral phenomena on the scene today. Many of us believe very clearly, that the concept of Black Power has this firm intellectual base, and it is not to be tampered with or toyed with, by glamour seeking editorial writers. Or the irrelevant Huntley and Brinkley types, who see only the burn, baby burn, or the honky talk.

Let me deal with my first now. In terms of the relationship of Black Power to the concepts of alienation and political modernization. Professor Seymour Lipset, wrote a book once entitled Political Man. And in that book, he talked about alienation. And he said, when the institutions of a society do not coincide with the values and aspirations of particular groupings in the society, then those institutions will be considered illegitimate, and those groups will become alienated.

Now, that's Lipset writing in Political Man. He followed it up a little later in the book and titled The First New Nation where he talked about alienation as having to do with the payoff — very simple, you see. and the important point to make here is this: A society, that is to say the institutions of decision making in a society, are legitimate or illegitimate, depending on the perception of the people relating to those institutions.

So in this instance, I'm going to say very clearly, that it isn't important what white decision makers say when they say we're making progress in race relations. What is important is what Black people perceive. And if it is in the life experiences and perceptions of Black people, that progress is in fact not being made, then those institutions will be perceived as illegitimate, all the other rhetoric notwithstanding. Now, we throw this word alienation around very loosely, you see, but I think it's the function of you and myself to just tighten up a little bit — not get up tight, but tighten up the language.

Now, there's another concept here that I like to deal with. And that's the concept of legitimacy. Professor David Apter wrote a book recently, and I'm sure in this kind of in this audience, I feel very much at home citing all this literature because your reputation is broad in the land, and you can handle it. And I know very clearly you didn't come and expect to hear this kind of level of presentation, but I'll get to the nitty gritty in a little bit. David Apter wrote a book, a very excellent book, entitled The Politics of Modernization, wherein Dave Apter was dealing with the whole phenomenon of political change, political development, essentially, in underdeveloped societies. Namely, in this case, because he is a student of Africa, African societies — Uganda, Ghana. But the important thing in that book is that Apter said very clearly, that when one is speaking about political legitimacy, one must be talking about normative values first, and structural arrangement secondly.

And then he went on to indicate, to set out what he would concede to be two principles of legitimacy. One he called the egalitarian libertarian principle, which is essentially associated with Western societies, societies that have already developed in a certain kind of socio economic and political way, societies taking much of their philosophical orientation from John Locke, you know, man is basically rational, capable of knowing his self interest, and capable of reaching accommodations based on that self interest, and so forth and so forth. The first principle of legitimacy has something to do with the Madisonian Model, as he set it forth in Federalist Paper number 10. You know, where there is a multiplication of factions and these factions contend with each other within a certain set of rules of the game.

And then there is a second principle that Apter talked about, fulfillment of potentiality. This principle is essentially associated with groups on the make, with societies moving out of colonialism into days of independence. Societies, which are beginning to feel their oats and are marching to modernity, if you please. And I'm going to suggest to you in no uncertain terms, that for Black people massively in the ghettos, we are going to adopt a principle of legitimacy which speaks to the fulfillment of our potentiality. Black Power says in no uncertain terms that we are not going to get hung up on this myth of individualism. And we're going to proceed very clearly now, around a concept of group development, group fulfillment, and this is the principle which is legitimate to us.

Alienation and legitimacy then, and then as I proceed, please, and as you ask your questions, keep that context in mind. Otherwise, I shall be forced to give you a C-minus or something like that.

Now, a lot of people in terms of this whole notion of alienation, for instance, an awful lot of people see Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brownand many of the others as now on the platform shouting 20 for One and burn baby burn, but what a lot of people fail to understand is, they failed to ask the question, where was Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap 3, 4 and 5 years ago, I'll tell you where they were. They were in Mississippi and Alabama doing watch the language, very systematically oriented things like engaging in voter registration, like holding freedom schools.

And I was working with Stokely in Greenwood, Mississippi one summer, and we had the audacity to actually play a game with ourselves, a serious game of seeing how many snick workers could file the most petitions to the Justice Department alleging voter denials as if those petitions accumulating one on one made a damn bit of difference to the Justice Department. The point I want to make here is this. If Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown are way out and alienated today, it is precisely because the society was illegitimate to them then and failed them.

Now, let us be clear about that point. And those Black people played the game according to the rules. They formed their or they registered their people. They formed their organizations, and they tried to get in to the regular party in Mississippi. They were rebuffed, obviously, look what happened. And so they did if you if you believe in Mr. Hobbs, you'll act rationally to defend your self interest. So they formed their own political organization called the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, what else would you have them do? Some people said parallel structures, separatists, segregation in reverse. Irrelevant language. This was Black people trying to survive.

And they took their demands, their legitimate demands, to the convention in August of 1964. And if any of you want me to pinpoint specifically chronologically, where masses of Black people fit began to fit in with Lipset's definition of alienation, I'll say it was on a broad walks of Atlantic City in August of 1964. Here theFannie Lou Hamersand the Virginia Grays working like hell all those years in those cotton fields, came to that place at that time, and presented their demands proving in no uncertain terms, that the Democratic Party in Mississippi was a racist segregationist party, and all those white liberal allies agreeing with them, but copping out at the last minute. Sayin well baby you know, we just can't quite cut it because you mess up our process.

And if you really want to know when Black people began to tune out of this system, on a massive scale, date it August 1964, check out Jean Smith's article in Redbook magazine for September last year, entitled "How I Learned To Be Black."

In other words, the point I want to make here is this, this society cannot continue to toy with the values and the aspirations of a people and expect that those people to continue to bestow allegiance on that society. It ain't about to happen, you see? And if then the demands get escalated, from voter registration to molotov cocktails, from freedom schools to guerrilla warfare. Don't let any white American scratch his head and wonder why. It is because the system has copped out on Black people, and Black people are not going to take it anymore.

So let's just stop right now asking these irrelevant kinds of questions about Hamilton, do you advocate violence? Baby, I don't have to advocate it. All I got to do is observe it.

Because Black people don't care what a PhD professor says, on a platform to a college crowd. We could be less than irrelevant. So if I come on here and say now, 'No, I do not advocate violence.' Do you think that's going to make any difference in Chicago on the west side this summer? You see.

Now Black Power says very clearly, that we don't have to relate to either the expressive or instrumental acts of violence. What we can do some of us can do is to attempt to offer this society a reasonable potential way out. And that moves me to my second point as Black Power as seen as a phenomena in the political monetization process.

I take here my context from Sam Huntington's work on modernization. And he says all societies undergoing the process of modernization are involved in three major phenomena. First is the process of centralization, the accumulation of power to the center. This is an ongoing process. We saw this with the breakup of the feudal estates and so forth. And indeed, that's what was happening. I suspect in those 17 hot weeks in Philadelphia in the summer of1787. The modernizing process then is a constant, one of centralizing authority.

The second phenomena of political modernization is the constant search for new values and new forms of decision making. Any society that would opt for modernity that rests on existing values and existing structures is a dying society. So a society must constantly be in search, reevaluating values, retesting reexamining its established institutions. And third phenomenon is the constant broadening of the base of pulling political participation. Any society that is not engaged in these three ongoing phenomena cannot call itself a society in the modernizing process.

Now, Black Power speaks very clearly to these three phenomena. We believe, first of all, that going back to Apter's statement on normative values first and structural arrangement, secondly. We believe that Black Power says very clearly that the traditional civil rights movement has failed to do one thing in this country, basically. Not that it was wrong in its thrust because, I conceive it as definitely right in its thrust, namely, knocking over segregation laws and so forth. But the traditional civil rights movement made a mistake. It assumed that the existing value structure of the society was legitimate.

And this is why Gunnar Myrdalis wrong 24 years ago when he wrote his book, American Dilemma. He said that there was a dilemma between creed on the one hand and practice on the other, that there was a hang up between what Americans said and what how Americans live. That's nonsense. As Charles Silberman said in his book Crisis in Black and White, white Americans don't go to bed nights worrying about how they treat Black people. They treat Black people precisely the way they feel Black people should be treated. They go to bed nights, Silberman said, because they're worried about law and order and stability. The point I want to make here is this, that we don't point to the language of the Declaration of Independence, the first three paragraphs or the 13th, and 14th amendments to decipher what America believes. You see, we check out their action. And so then, when Stokely and I write in our book, the first page of the first chapter in our book, and style this society one of institutional racism, people just sort of read over that real quickly and never come back to it because they're waiting to see what Stokely has to say about honkies and burn baby burn. And the the concept that we introduced of institutional racism does not get legitimized until the Kerner Commission Report comes around and calls this white racism...and didn't give us a footnote.

The point Black Power makes is this: very clearly, we will not spend our time and energy socializing Black people into the existing structures of this society, because the existing structures of this society are institutionally racist. And if we, if that's what we want to do, then we shall have none of it.

We are questioning the normative values of this society. This is a materialistic, parochial, insecure society. And the fact that we can build skyscrapers and shoot for the moon and beat up little children in Vietnam has nothing to do with her basic humanity. This is an illegitimate society. And it has nothing whatsoever to do with our economic affluence.

We say very clearly, that the major institution, the major movement, questioning the values of this society is Black Power. Labor movement doesn't do it. The churches don't do it. You know. You tell me any agency or institution in this society that has called into question the values of this society, and I will have to agree with you. Tell me one.

It wasn't until Black Power came along and began to really say this far no further, you are racist. You know. Now once you accept that, let's get on and see if we can work out a rapprochement.

But we must deal with the normative values first, before we move to structural arrangements. We believe that it will be the intervention of these legitimate Black Power groupings in number two, that will link up the broadening base of participation on the one hand with the centralizing forces on the other.

And if anybody believes that all this politicizing of masses of Black people like say in the south or like say in Chicago, that all what we're doing is bringing people massively into the political process, and then to deliver them over to the Dick Daleys of Chicago, then we would be anachronisms because the Dick Daleys of Chicago... are irrelevant.

And we would not be truthful to ourselves if we insisted on supporting those kinds of organizations. We see then, the centralizing process going on, we see the broadening of the base of political participation going on, not just electorally, but there are an awful lot of little Black people around running around now shouting Ungawa Black Power, that's part of the politicizing process. You see.

There an awful lot of Black people going around now wearing naturals and dashikisand going through funny handshakes. That's part of the politicizing process.

And I'm not going to let anybody tell me that it's ersatz. But it's make do it's make believe because I'm not going to let anybody tell me how a people who have been deliberately oppressed and suppressed how they should go about getting themselves together psychologically. If we want to wear our naturals baby we going to wear them. And if we want to go through our funny handshakes and our little Black caucus meetings, we're going to have it.

And we're going to TCB. I see no other viable organizations in this society that can give meaning to Black people as they come into the political process. Now, I brought one piece of information with me just as a kind of documentation. I read it on the plane today, man. This is the Chicago Daily News, they can be so relevant at times. And you know, I was on the O'Hare Airport and I read I got a paper expecting to see if the White Sox had ever won a ball game and so. If you if you want to know my other hang up, I'll tell you about that one. White Socks. This is called recess. You see I have a style that permits you to step back a little bit. Just relax you know. You ought to dig some of my goodness away or just cool it now. This is an article entitled "Absentee Bosses Rule Westside Ghetto." And it shows how, in 75% of the precincts in the wards in West Side, Chicago, do you know who the bosses are? Who the ward commitment are who the precinct captains are? Whites.

Query? That's a legal term query, Where do they live? 1040, 1040 Lakeshore Drive. It's a very interesting article. Very interesting. It's an expose. Something we knew all along. But now you'll see the press is are getting in on the act. That's all right. Everybody's got to do his thing, you know.

And this article points out very clearly, very, very clearly, you see that all of the decisions, the political decisions are made by absentee political, slum lords. Lords of the riot area, they don't even live there. And they have fictitional address, and these are the people Dick Daley would relate to, you see. These are the people that he feels represent the Black communities. Well Black Power is saying let's be done with that nonsense, because, you see, as long as we continue to think that we are existing in a society where the institutions of decision making are legitimate, then we shall continue to be deluding ourselves and turning on and frustrating further Black people.

So when Mr. Daley gives a shoot to kill order, let it be very clear that the only thing he has done is to reinforce the thinking of many Black people, that the only alternative is to shoot some whites. Now, let that be clearly understood. Now.

So let us see then, this whole Black Power thrust as a move toward the modernizing process. And if anybody wants to point out to me, some other legitimate kinds of organizations which can fill that gap, which can move in in terms of number two, the search for new values and new forms, new organizations and new structures, if anybody wants to come up with new ones as a George Meany's AFL CIO. Is it the Republican Party on the west side of Chicago?

We must begin to put to ourselves some terribly, terribly hard questions. Less I assure you, we are playing at school. Now, a lot of this can sound very contentious, and my demeanor could be one of bitterness. But let us keep in mind at all times, I'm speaking about political modernization.

The third point I want to make, and then I'll stop, is let us move now to some programs of Black Power, generally, and a few of them. Everyone says Black Power is basically rhetoric, you know, that we're long on language and short on action. Everyone's because that's what what they're really doing, you see is focusing at the visible level. They see cats like myself, come on and rap, you see, and they see Stokely, and that's about all they see. But they don't see us. And occasionally they'll see a Dick Hatcher getting elected in Gary, Indiana, and let the record show here very clearly, that Dick Hatcher is mayor of... and this is Black Power in operation. Okay, that's what I'm moving into — programs.

Dick Hatcher is mayor of Gary, Indiana today, and a lot of people will say, ah, but with 17% of the white vote crazy, correct? You're right. But Dick Hatcher would not be mayor of Gary, Indiana today, if he had not started out seven years ago building a base of Black Power, independent Black Power in Gary.

And if there's another footnote to this, we can add it right here. I think that it's a commentary on the times in Gary to that if if Dick Hatcher were white, there never would have been any question because the white Democratic candidate always wins. Blacks had to get themselves together first in Gary, Indiana, before they could even begin to talk about political power.

Now we are in the process of running candidates now across this country. Independent candidates in the third congressional district in Chicago. Gus Savage is running against the incumbent Democratic candidate. And we've done our counting, we know where the votes are, we know how to do voter registration, and we're going to win. That's very clear. Because you see, we're through fighting symbolic races. We're through trying to get on the ballot just to raise the issue. When we sink our time energy and money into races now around this country, at any level, it's it's gonna be a we're gonna have a good chance of winning. Now, a lot of people will say, but look, man, what is one more congressman gonna mean? They're 435 or so remember? or more...

Now, I was fully aware of my Marxism as anybody else. But I know that he who would act would now would not deal in the Millennium question. I know here now very clearly, that when I go back to Southside Chicago, at 63rd and south park or 63rdand cottage, or 43rd and Langley, and if I want to organize Black people now, I've got to organize them around what they can see to be relevant in their lives now.

You see. If you want to philosophize with me about the millennium question about knocking over the exploitative capitalist system, crazy man, check me, I'll make an appointment, I'll take my seminar. But if you're going to move with me into the Black community now and attempt to organize, then you better check out your actions. You see, some of us are getting awfully sick and tired of having a philosophy imposed upon us and then have having that philosophy immobilize us. We will work out our own damn philosophy, and we'll do it in our time and in our way. And if anybody in here thinks that that's a Marxist cop out, let me tell you very clearly, what I'm pushing for is a Black Power variant of Hamiltonism, to hell with Marxism. Alliances? Of course we'll make alliances. Surely we'll make alliances.

But as we say in chapter three of that excellent, excellent book... we will make alliances on three conditions. First of all, we will definitely not enter the kinds of alliances that we found ourselves hung up with in August of '64. Like when Walter Reuther and Hubert Humphrey and the National Council of Churches and all those other cats moved out on us, all we could do was hang our heads and sing "We Shall Overcome." We're not going to be involved in that sort of nonsense again. We will enter alliances with very sincere people. First, however, after we establish our own base of independent power, whereby if that partner in the alliance cops out on us, we will have power to punish him. Let us understand that.

Now, what do you mean Hamilton, I mean very clearly, that when Ab Mikva for the 2nd Congressional District in Chicago, wants our help, it will be reciprocal. And if he fails to help us in the third congressional district, then we'll blow the whistle on him and pull people out of his race in a second. That's the way you work alliances. Secondly, let that be alliances sure we'll enter alliances, but on a very clear terms, that it's not just unilateral. Not whites bringing their altruism to us. But we must, it must be very clear that there is mutual self interest involved here. We will enter alliances with those whites who perceive that they have a self interest which can which is akin to ours, or where the quid pro quo can operate.

Up to now we've been coming to whites begging, pleading, and whites have seen it in their hearts to help us or not. And more frequently than not, we've been left in the lurch.

The third, yes, we'll enter alliances on the condition that it's clearly understood that these alliances are ephemeral and here yes, the Madisonian model does work. The factions will break up and regroup from time to time. We ain't about to become nobody's puppet, if I can use that double negative, as we are now on Southside Chicago and the Democratic Party. They've got us in their hip pockets, and can deliver us every first Tuesday, right on the nose.

So when we form our own separate organizations, our political organizations, go ahead let people call it separatism. It's the most healthy kind. We had better separate ourselves from some of these anachronistic and oppressive institutions if we want to get our minds together. Alliances, sure we'll enter alliances, so we don't have to get involved in that polemic about what can whites do, you can go infiltrate the white community, help to end racism there, develop viable groups there and hook up with us. That's what you can do. So we can just stop that question right now.

You see, I get so sick and tired with people who always relating at the non practical level, you see, right away, somebody will say, well, like if you gonna do your thing? Is this permanent separate — you know, all that sort of read Martin Dugelman's article in Paterson Review, I guess it's a fall the last issue before that some of us came back in answer to this, read that article. Here's a very intelligent man professor at Princeton and all, you know, he's supposed to be into something. You know, he got some insights, wrote an article on Black Power... copped out at the end. You know. It's nonsense. It's really nonsense.

We get to the point and in dealing with this subject, that we can just over intellectualize it, you know, we overreact to it. All these questions on alliances. How can we work with each other and so forth? That comes from people who never really know what action is.

You put together, Dick you work with Dick Hatcher, in his campaign, you'll see very clearly how alliances can be worked out, and when they can be worked out. You go work with another group, SCLC's operation breadbasket in Chicago, and you'll see very clearly how whites can work and how alliance alliances can be formed.

The point is, you ain't about to get it by simply reading some of these articles, except some of them... or many of these books you see, except some. What is Black Power programmatically? It's like SCLC's Operation breadbasket, where they organize Blacks through the churches, to boycott merchants and manufacturers who do not hire and promote Black people. Very clear started by Leon Sullivan back in 1961. Blacks do have some consumer power, and they mighty sure are going to use it. And in Chicago alone through just Jesse Jackson's SCLC, Operation breadbasket, 2000 jobs we've gotten for Blacks in a 15 month period, with an a total annual income of $15 million. Other people say but man, that's again, piddling well, you know, what alternative? Black people start where they are and move where they can. Are you talking about Coor's burgeoning co-ops throughout the south, many of these co-ops started on an integrated basis one in Opelousas, Louisiana a co-ops of cabbage, sweet potato and okra growers. 20% whites were in this co-op three of two, two years ago. Now it's all Black not because the Blacks kicked them out not because the Black farmers and there are 300 Black farmers in this co-op not because and they're surviving and and really developing credit unions buying clubs and so forth. They, it's not all Black because the whites, they kicked the whites out. But because the white farmers felt so much pressure from the townspeople that they got out of it for that reason. And this is being done throughout the South. No, no, no, not millions of people, but it's starting now you don't hear about this or read about these things in Huntley and Brinkley, you see or some of your pop journals. You read about Black Power as the Mau Mau coming down the streets of Grinnell, Iowa.

Are you talking about other Black Power groups? Let me talk about one that's not on the drawing boards, but that's out there working, Black professional middle class people. Now you hear a lot about this, how Black professionals have opted out. To a large extent that has been true and still is. But let me say in no uncertain terms, that where I come from and where I go, I see Black professionals getting involved in the Black movement en mass.

We formed a group of Black professionals in Chicago, January 20, called a meeting 371 Blacks came was Southside Presbyterian Church, met all day, lawyers, three doctors, accountants, physicians, teachers, social workers, and so forth. Each dealing with his own field and talking about and drawing up ways whereby they can be relevant to the Black community, and then linking up with the WSO organization, Westside organizations, and the other grassroots Black groups bringing their skills to bear. And the first major test of whether the catalyst group is what it's called, could do anything was right after Dr. King's assassination in Chicago.

45 Black lawyers coming out of this brief organization that we have formed 45 Black lawyers, went down and insisted that those despicable processes that were being pursued by the Chicago system judicial system be immediately ended.

Chapter 13 of the Kerner Commission Report spells out certain legitimate ways the machinery the judicial machinery should operate. After or during an emergency period like a riot. Chicago was in the process of operating just the opposite, holding people incommunicado for days, $50,000 bonds and so forth. These 45 Black lawyers mobilized overnight, brought pressure, got grassroots groups behind them, and insisted that the court open up, start hearing these cases. And they insisted even that they hold court on Easter morning, Easter Sunday morning and 300 cases were heard there. And let me tell you, these Black lawyers in Chicago didn't charge a penny. That's Black Power. And that's what we're doing.

You don't hear about this. Because I'm going to tell you very clearly, a hell of a lot of what we do ain't about to be pulled off successfully at no press conference. If we really got to get ourselves together and get operating and get moving, then we start to act. And that's what I'm coming here to tell you we're doing.

Other organizations, the Association of Afro American Educators, first of all, those are those are Negro teachers. And if you know anything about the Black middle class, you know, for them to start calling themselves Afro Americans is a revolution in itself.

Growing organizations around this country, talking about, what, the Coleman report? Nah. The debate between Tom Pettigrew and Joe Alsop, at The New Republic on ghetto education? Nah. Uh uh. Let those whites go on and hold their irrelevant discussions. They haven't been near the ghetto in 10 years anyway, and then via telescope.

Black teachers are meeting now forming their own organizations. Rewriting curriculums in those Black high schools and those Black elementary schools because they know what kinds of education is relevant for Black children. They teach them every day. They live in those Black communities, you see. And we don't need any massive reports coming down from Harvard or Johns Hopkins or any other place to tell them to tell the Black teachers caucus at Hyde Park High School, for instance, what's relevant in the curriculum in Hyde Park High School in Chicago. And that's what's happening. And I get pummeled with this. And these people are in fact, the legitimate ones. They, my friends, are your number twos and the modernizing process. Now let that clearly be understood.

Black social workers are forming, working with welfare unions. Now look, I could come on here and you know, and turn you on and say and make try to make you believe that this is happening en mass, you know, and that as soon as you get outside of Grinnell and move into a major urban area, you're going to be bombarded with this new Black modernity. Nah, no. Cool it now. Not really. But it's starting. It's beginning, you see. And that's why I can be so optimistic, because I see for the first time, Black people with skills and Black people hooking up the haves hooking up with the have nots, I don't know where that fits in that other kind of philosophical orientation, but I see it happening.

Call it petty bourgeoisie, anything you like, but I see it happening and I know the kinds of demands they're making Black control of the institutions of their community like IS 201. Some of us are absurd enough to come up with some vast gross new kinds of plans for education in the Black community. I wrote about it, you can check it out.

But fundamental to all, all of this, you see fundamental to all of this is we don't want to talk just as Monahan talks, or as a lot of other people talk. We don't want to talk just in terms of an equitable distribution of goods and services. Those people are rioting give them more jobs. Those people are rioting, give them more houses. Those people are rioting give them better schools. No, no, no, no. That's not just what we're talking about. Because if you think only in terms of give em give em give em, then you are perpetuating a welfare mentality. And Black people should know anything, he who giveth can also taketh away.

So we are saying very clearly as we go about the business of developing these organizations, and getting them off the ground in the Black community, don't you just talk in terms of an equitable distribution of goods and services, until the society is legitimately prepared to talk in terms of an equitable distribution of decision making power, then this society is playing at school. And that's what we're pushing for. And that's what we're gonna get.

It's not like Governor Otto Kerner back to him, different commission though, or later one, you know about the Kerner Commission Report on civil disorders.

Last week, Governor Otto Kerner appointed in the state of Illinois, a commission on urban area government, calling for a study by this 54 member commission, quote, "to see how to make to restructure the government in the state so that the government could be more responsive to the needs of the people." 54 member commission. Two Black people on it. One is Ed Berry of the Chicago Urban League, and the other is an associate dean at Northwestern University.

Not one legitimate representative, elective or otherwise, of the Black ghettos. Now if, so apparently governor Kerner didn't learn a thing. So we're saying to that man and to others, decision makers like him, if you think your commission can do anything legitimate, about finding out what you want to find out, and then subsequently about implementing them, without legitimately involving and consulting and including Black people, at the relevant levels, then you are mistaken. Now this is what we're talking about you see. We've got to stop this nonsense, whereby decisions can legitimately be made over the heads of and without the consent of Black people.

Finally, there is the cultural emphasis of Black Power, which is the most crucial one. And again, you see it goes back to what I can see it to be the the major innovative thrust of Black Power, where I distinguish it from the traditional civil rights groups. Black Power talks, in terms of Black is beautiful, and in a sense, I tell my eight year old, she is beautiful because she is Black.

Black Power is clearly aware and agrees with Stanley Elkins, when he talks about the development of a Sambo personality and how slavery did that. We are aware of Bruno Bettelheim's studies on the effects of the concentration camps on Jews, some Jews. Where both of these men talk about in their studies and I'm sure you some of you read about this what happens to the psyche and the mentality of an oppressed person in a highly structured, rigid and closed society where the guard, the master stands between him and death? He develops a Sambo personality a childlike personality, as Bruno Bettelheim pointed out to describe some of the Jews developed in these concentration camps they began to mimic, act like walk like look like the SS guards.

And we know enough about Black people in this country to know that a hell of a lot of them have tried to be still try to be like whites. We know that. We know that forever so long is Killian and Grigg point out in their book Racial Crisis in Americaand it still means that integration means adopting to the white man standards. Integration means trying to act like whites.

Were saying no, no, this far and no further. If that's what integration means that day has done and that deed is denounced. We're saying very clearly, that we are Black people, and we are proud and we are self confident. And people like myself, who have how many degrees, I got a Bachelor's, check it out, law degree, MA and a PhD, I went that route, you know. I did everything right.

And now I stand up here talking like this, I must be some kind of freak because I should have been socialized into the mainstream.

I would not be, I could not go home nights and face my little eight year old daughter if I began to spew a lot of that nonsense I learned getting my PhD.

Now I'm not, I'm not coming on anti intellectual. I say this to your fessors. I'm not being anti intellectual. I'm just saying let's begin to redefine the legitimacy of intellectualism. Let's just rush to relevancy in no uncertain terms.

A little story then I'll quit. Went through law school, never occurred to me, that law school Loyola, Chicago that was learning anything relevant to me as a Black man and a future Black lawyer in the ghettos. No landlord and tenancy, no rights of the indigent. They loaded me up with future interests, estates, property, trust law. And now many of these law schools are trying to rush to relevancy by developing Urban Studies centers a euphemism for the Black thing.

I went to get an MA and a PhD at the University of Chicago, it never occurred to me that those people were writing stuff relevant to what was happening in the ghetto, the Black ghetto where I was living in Woodlawn. Never occurred to me. And when I went on to get my PhD, write my PhD dissertation, my advisor, who is still there, and chairman of the department today, so well, Hamilton, what are you gonna write about? I said well baby, you know, I gots to do something about my people. First of all, I shouldn't been talking like that, because I'd gone far enough to know that how to speak correctly. So he said, well, what do you have in mind? So I said, well, you know, I'd like to do something on southern federal judges and the rights of Black people to vote. He says, well, that's okay, fine, you can get a lot of good data from the Justice Department. But he says Hamilton, I wish someday you would rise above that... this is this man's there, now, white liberal friend of mine, and become more universal. I'm looking for the day when you will write something on, for instance, the British parliamentary system. Well see that man, so that man was willing to let me write about my people, you see, but never considering that that was really relevant. Uh he didn't understand and doesn't understand today the subtle racist implications of that comment. And I doubt if there's a Black person in this room who's lived in this country more than a week and a half, who hasn't been presented with some sort of insult of that nature, that if you are Black, that the thing you want to be is an individual and not a Black person. Let me say here very clearly, for the record, I'm not a political scientist who happens to be Black. I am a Black political scientist. I'm not a college professor who happens to be a Negro. I am a Black college professor, who's chairman of his department understand.

The final point I want to make then and I'm thinking that it's just about 45 minutes. Black Power says very clearly, that we are no longer in the business of turning out middle class Blacks sambos. We've got ourselves a thing to do. And if my demeanor, and if my language is somewhat slightly askew, let me tell you very clearly, that's Black Power, too, because we come to do our thing. And let me tell you finally, where I come from 46 and South Park, we got a saying that goes everything gon be alright.