Kimbrly Orea Badillo gave birth to her second son on Mother’s Day in Des Moines, Iowa.

She already feels like she needs a lot of support.

“I feel like…I don't get sleep,” she said. “I feel like I need to talk to my doctor more about it, just to make sure I'm doing okay.”

For the past month, the 20-year-old has been juggling taking care of a newborn and his older brother, who turns two in July, as she recovers from a cesarean section.

She relies on Medicaid to afford her postpartum care and prescriptions, like birth control and pain medication for her C-section wound.

“I have to take them every four hours if I feel pain, so that's helping me,” Orea Badillo said. “And if it wasn't for Medicaid, I wouldn't get those at all. I would have to pay the full price for it.”

Federal law requires that states provide Medicaid recipients like Orea Badillo with 60 days of postpartum coverage.

But starting in 2021, under the American Rescue Plan Act, the federal government offered states the option to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to a year. The move comes with permanent matching federal funds.

More than 40 states have adopted the policy so far, including nearly all Midwestern states like Kansas and Missouri. It’s received wide bipartisan support overall. But a handful of Republican-led states like Iowa, Idaho and Arkansas, recently ended their legislative sessions for the second time since the extension option has been available without approving the extension.

This has left some medical professionals concerned that the most vulnerable, low-income women won’t get the postpartum care they need. It would happen at a time when thousands are at risk of losing their Medicaid coverage following the end of the national public health emergency this spring.

Vulnerable patients

Leading medical groups, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have long recommended all moms receive at least a year of postpartum care.

“We know for many measures of someone's health and physiology that it can take up to 12 weeks before you're even back to a normal, non-pregnant physiology,” said Stephanie Radke, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Iowa.

Postpartum care is mostly preventive care, which includes screening for any complications, such as postpartum depression, and treating them before they hit a crisis point, Radke said.

Postpartum moms on Medicaid are more likely to have poorly-managed underlying medical conditions, like hypertension and diabetes, that can be exacerbated during pregnancy.

“Within 60 days postpartum, they may or may not be back to their baseline level of health that they entered pregnancy with,” Radke said. “And so they really have a need for care that's really continuous.”

In recent years, the U.S. has experienced rapidly increasing maternal mortality rates.

In 2021, the U.S. had 32.9 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, an increase of 40% from 2020, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It’s a historically high maternal mortality rate and is significantly above the rates of other high income nations, such as Australia, the Netherlands and Japan, which all had rates below 4 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020.

Black Americans, who are disproportionately more likely to be on Medicaid, were 2.6 times more likely to die during or after childbirth than non-Hispanic, white Americans in 2021, according to the CDC.

“There can be a lot of changes related to emotional well-being, sometimes that swings to the point of postpartum depression,” Radke said. “And just kind of figuring out how to integrate their new self as a mother and as a caregiver for a very vulnerable human is not always something that everybody has completely figured out by 60 days postpartum.”

Iowa the holdout

The one-year postpartum extension has been popular nationally with lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

“The time is ripe right now,” said Joan Alker, the executive director of the Georgetown Center for Children and Families. “We see there's so much concern about the state of maternal health. We've seen a worsening of maternal mortality in this country and some really shocking and troubling trends, particularly for women of color.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade last summer has contributed in part to more lawmakers’ interest in policies that address child and maternal care overall, Alker said.

A number of Republican states that have mostly banned abortion, like South Dakota, Missouri and Mississippi, have also passed the 12-month postpartum extension as part of a push to support childbirth.

Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves said passing the extension this year was part of the state’s “new pro-life agenda.”

This month, Nebraska lawmakers approved a postpartum extension of “at least six months” leaving it up to the state Department of Health and Human Services as to whether it will ask the federal government for the full 12-month extension. State officials haven’t said what they are planning to do yet.

“I don't know if I've ever seen such widespread bipartisan embrace of a policy, as we've seen for this 12 month postpartum policy,” Alker said.

But some lawmakers in states, like Iowa, remain hesitant about it.

In Iowa, 25% of pregnancy-related maternal deaths in 2021 happened between 43 days and one year after birth, according to a review by the state’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee. The committee determined all of those deaths were preventable.

A legislative fiscal analysis in 2022 estimated Iowa’s share of the extension will cost about $9 million for the 2024 fiscal year.

Iowa Republicans, who control the legislature, have a number of concerns about extending postpartum care to a year, according to state Rep. Ann Meyer.

She said, for one, Iowa already has the highest income ceiling in the country for pregnant women to get on Medicaid.

“We're most focused on providing a safety net for those people who need it,” Meyer said. “Our caucus also believes in balancing that without creating more government dependency.”

Iowa lawmakers have also been slow to adopt the extension because the national public health emergency, which barred states from disenrolling anyone with few exceptions, she said.

However, this requirement ended in April, and now states are undergoing the process of unwinding, or removing those from Medicaid who no longer qualify.

Meyer said that the legislature will consider a postpartum extension policy again in the 2024 session.

In the meantime, in states like Iowa that didn’t approve the postpartum care extension, many moms on Medicaid going forward will go back to only two months of coverage.

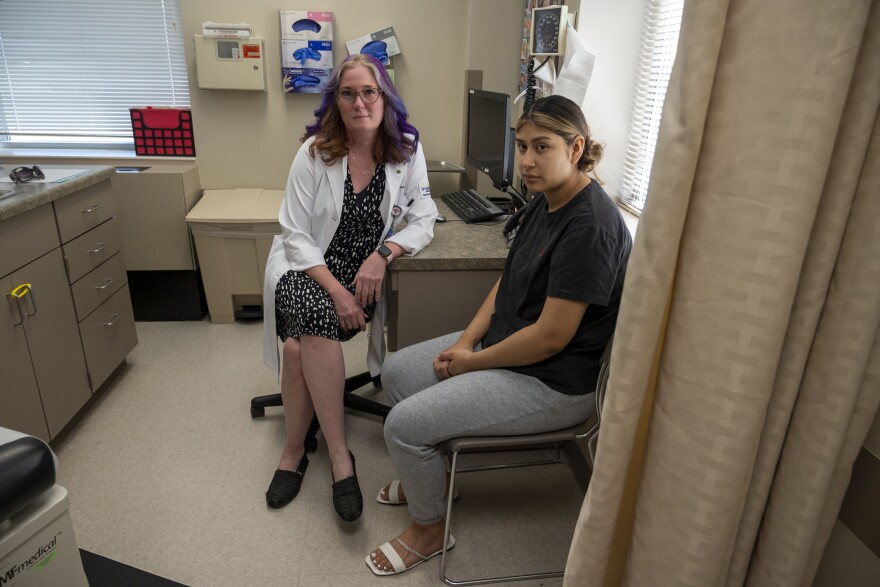

Francesca Turner, an OB-GYN who works at Broadlawns Medical Center in Des Moines, said a shift back to two months of postpartum care coverage would be devastating.

More than half of the maternal health patients at her clinic are on Medicaid.

“I feel like we work really hard to keep people safe and keep people cared for and then you get them to that point, and they lose their health insurance, and it just almost unravels,” she said.

Turner said many of her most vulnerable patients may be unaware they may be losing postpartum coverage in the next couple of months.

“They can't get access to contraception. They can't get access to their follow up pap smears. They can't get access to whatever health care they need.”

This story comes from a collaboration between Side Effects Public Media and the Midwest Newsroom — an investigative journalism collaboration including IPR, KCUR 89.3, Nebraska Public Media News, St. Louis Public Radioand NPR.